Volatile compounds in distillates and hexane extracts from the flowers of Philadelphus coronarius and Jasminum officinale

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15587/2519-4852.2024.318497Keywords:

Philadelphus coronarius, Jasminum officinale, essential oil, component compositionAbstract

Jasminum L. of the Oleaceae family is a genus of plants cultivated for its aromatic flowers, which are a source of essential oil (EO). In temperate countries, jasmine, or pseudo jasmine, is often called Philadelphus coronarius L. of the Hydrangeáceae or Philadelphaceae family due to its similar fragrance.

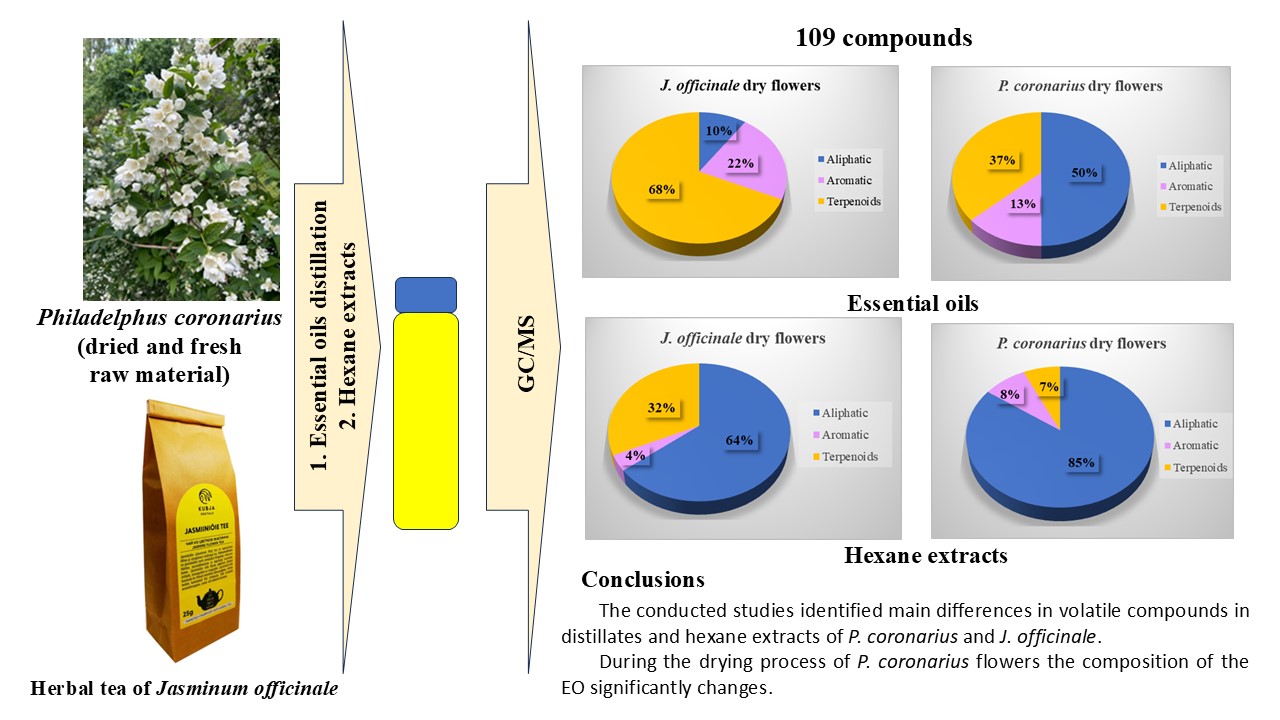

The aim. The aim of the study was to compare the component composition of volatile compounds of hydrodistillates and hexane extracts from flowers of Philadelphus coronarius L. and Jasminum officinale L..

Materials and Methods. Hydrodistillates obtained from dried flowers of J. officinale and from dried and fresh flowers of P. coronarius, as well as hexane extracts from similar raw materials, were analyzed by GC-MS.

Research results. 109 compounds were identified. It was found that in the EO of J. officinale, obtained by hydrodistillation, the terpenoid content is 90.31 %, while in the hexane extract of the same raw material, the terpenoid content is only 36.24 %. In the EO of P. coronarius, obtained by hydrodistillation of dry flowers, the terpenoid content is 50.04 %, and from fresh flowers – 45.13 %. In the hexane extract of dry flowers of P. coronarius, the terpenoid content is only 14.63 %, while in the extract of fresh flowers – 52.55 %. In the EO of J. officinale obtained by hydrodistillation, the dominant components are (E)-geranyl linalool (12.86 %), linalool (10.72 %), (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol benzoate (7.82 %), α-farnesene (7.72 %), D-limonene (6.43 %), methyl anthranilate (5.9 %), (Z)-9-tricosene (4.15 %). In the EO obtained by hydrodistillation from dried flowers of P. coronarius, the dominant components are (1R)-(-)-myrtenal (12.73 %), myrtanal (11.09 %), pentadecanal (9.42 %), tricosane (8.33 %), (Z)-jasmone (7.09 %). In the EO, it is obtained by hydrodistillation from fresh P. coronarius flowers, the dominant components are: nerolidol (19.42 %), ethyl palmitate (19.13 %), methyl 2-methylpalmitate (16.44 %), myrtanal (9.91 %), pentadecanal (5.28 %), (Z)-jasmone (2.72 %).

Conclusions. The conducted studies identified the main differences in volatile compounds in distillates and hexane extracts of P. coronarius and J. officinale. A total of 109 compounds were identified in the objects, and the dominant components were established. During the drying process of P. coronarius flowers, the composition of the EO significantly changes. Only hexane extracts from dried flowers of J. officinale and P. coronarius contain triterpene squalene in significant amounts (13.96 % and 6.72 %). Common to the hexane extracts of the studied objects are aromatic compounds: benzyl alcohol, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol; aliphatic compounds: 2,4-dimethyl-heptane, octanal, decanal

Supporting Agency

- European Union in the MSCA4Ukraine project “Design and development of 3D-printed medicines for bioactive materials of Ukrainian and Estonian medicinal plants origin” [ID number 1232466].

References

- Harilik ebajasmiin. Wikipedia. Available at: https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harilik_ebajasmiin Last accessed: 10.25.2024

- Ebajasmiin (perekond). Wikipedia. Available at: https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebajasmiin_(perekond)

- Philadelphus coronarius L. Plants of the World Online. Kew Science. Available at: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:792194-1

- Philadelphus coronarius L. World flora online. Available at: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000465348

- Mucaji, P., Grancai, D., Nagy, M., Czigleová, S., Budĕsínský, M., Ubik, K. (2001). Nonpolar components of the leaves of Philadelphus coronarius L. Ceska a Slovenska farmacie, 50 (6), 274–276.

- Pető, Á., Kósa, D., Haimhoffer, Á., Nemes, D., Fehér, P., Ujhelyi, Z. et al. (2022). Topical Dosage Formulation of Lyophilized Philadelphus coronarius L. Leaf and Flower: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Assessment of the Plant. Molecules, 27 (9), 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092652

- Czigle, S., Mu[cbreve]aji, P., Gran[cbreve]ai, D., Veres, K., Háznagy-Radnai, E., Dobos, Á., Máthé, I., Tóth, L. (2006). Identification of the Components ofPhiladelphus coronariusL. Essential Oil. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 18 (4), 423–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2006.9699130

- Klecáková, J., Chobot, V., Jahodár, L., Laakso, I., Víchová, P. (2004). Antiradical activity of petals of Philadelphus coronarius L. Central European Journal of Public Health, 12, 39–40.

- Nagy, M., Grancai, D., Jantova, S., Ruzekova, L. (2000). Antibacterial activity of plant extracts from the families Fabaceae, Oleaceae, Philadelphaceae, Rosaceae and Staphyleaceae. Phytotherapy Research, 14 (8), 601–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1573(200012)14:8<601::aid-ptr771>3.0.co;2-b

- Dilshara, M. G., Jayasooriya, R. G. P. T., Lee, S., Jeong, J. B., Seo, Y. T., Choi, Y. H. et al. (2013). Water extract of processed Hydrangea macrophylla (Thunb.) Ser. leaf attenuates the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators by suppressing Akt-mediated NF-κB activation. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 35 (2), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2012.12.012

- Jasminum L. Plants of the World Online. Kew Science. Available at: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:328128-2

- Jasminum officinale L. Plants of the World Online. Kew Science. Available at: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:609672-1

- BSBI List 2007 (xls). Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-06-26.; "Jasminum officinale". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture.

- Makeri, M., Salihu, A.; Nayik, G. A., Ansari, M. J. (Eds.) (2023). Jasmine essential oil: Production, extraction, characterization, and applications. Essential Oils. Academic Press, 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-91740-7.00013-x

- Dinh Phuc, N., Phuong Thy, L. H., Duc Lam, T., Yen, V. H., Thi Ngoc Lan, N. (2019). Extraction of Jasmine Essential Oil By Hydrodistillation method and Applications On Formulation of Natural Facial Cleansers. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 542 (1), 012057. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/542/1/012057

- Jasmine Essential Oil Market Research Report (2021). Report ID: Global Forecast To 2028, 249. Available at: https://industrygrowthinsights.com/report/jasmine-essential-oil-market/

- Singh, B., Sharma, R. A. (2020). Secondary Metabolites of Medicinal Plants, 4 Volume Set: Ethnopharmacological Properties, Biological Activity and Production Strategies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527825578

- Rattan, R. (2023). Genus Jasminum: Phytochemicals and Pharmacological effects-a Review. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 10 (2), 787–795.

- Rattan, R. (2023). Secoiridoids from Jasminum Species- A Report. of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 10 (6), 104–109. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373709272

- Frezza, C., Nicolosi, R. M., Brasili, E., Mura, F., De Vita, D. (2024). Occurrence and Biological Activities of Seco‐Iridoids from Jasminum L. Chemistry & Biodiversity, 21 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.202400254

- Elhawary, S., El-Hefnawy, H., Mokhtar, F. A., Sobeh, M., Mostafa, E., Osman, S., El-Raey, M. (2020). Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Extract of Jasminum officinal L. Leaves and Evaluation of Cytotoxic Activity Towards Bladder (5637) and Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cell Lines. International journal of nanomedicine, 15, 9771–9781. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s269880

- Lu, Y., Han, Z.-Z., Zhang, C.-G., Ye, Z., Wu, L.-L., Xu, H. (2019). Four new sesquiterpenoids with anti-inflammatory activity from the stems of Jasminum officinale. Fitoterapia, 135, 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2019.03.029

- Dubey, P., Tiwari, A., Gupta, S. K., Watal, G. (2016). Phytochemical and biochemical studies of Jasminum officinale leaves. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 7 (6), 2632–2640. https://doi.org/10.13040/ijpsr.0975-8232.7(6).2632-40

- El-Hawary, S. S., EL-Hefnawy, H. M., Osman, S. M., EL-Raey, M. A., Mokhtar Ali, F. A. (2019). Phenolic profiling of differentJasminumspecies cultivated in Egypt and their antioxidant activity. Natural Product Research, 35 (22), 4663–4668. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2019.1700508

- Al-Snafi, A. E. (2018). Pharmacology and Medical Properties of Jasminum officinale – A Review. Indo American Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 5 (4), 2191–2197. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1214994

- Wei, F., Chen, F., Tan, X. (2015). Gas Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Essential Oil of Jasminum officinale L var Grandiflorum Flower. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 14 (1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v14i1.21

- Garg, P., Garg, V. (2023). Bibliometric Analysis of the Genus Jasminum: Global Status, Research and Trends. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 41, 100711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2023.100711

- Kaviani, M., Maghbool, S., Azima, S., Tabaei, M. H. (2014). Comparison of the effect of aromatherapy with Jasminum officinale and Salvia officinale on pain severity and labor outcome in nulliparous women. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research, 19 (6), 666–672.

- Mukhlis, H., Nurhayati, N., Wandini, R. (2018). Effectiveness of Jasmine oil (Jasminum officinale) massage on reduction of labor pain among primigravida mothers. Malahayati International Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 1 (2), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.33024/minh.v1i2.1590

- Saxena, S., Uniyal, V., Bhatt, R. P. (2012). Inhibitory effect of essential oils against Trichosporon ovoides causing Piedra Hair Infection. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 43 (4), 1347–1354. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-83822012000400016

- Al-Khazraji, S. M. (2015). Evaluation of antibacterial activity of Jasminum officinale. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences, 10 (1), 121–124.

- Rama, G., Ampati S. (2013). Evaluation of flowers of Jasminum officinale for antibacterial activity. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3 (1), 428–431.

- Balkrishna, A., Rohela, A., Kumar, A., Kumar, A., Arya, V., Thakur, P. et al. (2021). Mechanistic Insight into Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potential of Jasminum Species: A Herbal Approach for Disease Management. Plants, 10 (6), 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061089

- Khan, U. A., Rahman, H., Niaz, Z., Qasim, M., Khan, J., Tayyaba, Rehman, B. (2013). Antibacterial activity of some medicinal plants against selected human pathogenic bacteria. European Journal of Microbiology and Immunology, 3 (4), 272–274. https://doi.org/10.1556/eujmi.3.2013.4.6

- Bera, P., Kotamreddy, J. N. R., Samanta, T., Maiti, S., Mitra, A. (2015). Inter-specific variation in headspace scent volatiles composition of four commercially cultivated jasmine flowers. Natural Product Research, 29 (14), 1328–1335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2014.1000319

- Issa, M. Y., Mohsen, E., Younis, I. Y., Nofal, E. S., Farag, M. A. (2020). Volatiles distribution in jasmine flowers taxa grown in Egypt and its commercial products as analyzed via solid-phase microextraction (SPME) coupled to chemometrics. Industrial Crops and Products, 144, 112002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.112002

- Lasekan, O., Lasekan, A. (2012). Flavour chemistry of mate and some common herbal teas. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 27 (1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2012.05.004

- Henno, O. (1995). Puude ja põõsaste välimääraja. Tallinn, 580.

- Kubja ürditalu. Aastast 1988. Available at: https://kubja.ee/ Last accessed: 10.25.2024

- European Pharmacopoeia. 11th ed. (2022). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Hrytsyk, Y., Koshovyi, O., Lepiku, M., Jakštas, V., Žvikas, V., Matus, T. et al. (2024). Phytochemical and Pharmacological Research in Galenic Remedies of Solidago canadensis L. Herb. Phyton, 93 (9), 2303–2315. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2024.055117

- (Z)-Jasmone. Available at: https://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/data/rw1016891.html

- Wasternack, C., Song, S. (2017). Jasmonates: biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling by proteins activating and repressing transcription. Journal of Experimental Botany, 68 (6), 1303–1321. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw443

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Raal Ain, Тetiana Ilina, Alla Kovaleva, Oleh Koshovyi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Our journal abides by the Creative Commons CC BY copyright rights and permissions for open access journals.